Today’s Fire Danger

Today’s Fire Danger – Burning Restrictions and Fire Activity Click Here

Burning permits: Wisconsin Burning Permits – Click Here

History of Wildfire: Major Fires in Wisconsin History

GERMANN ROAD FIRE | 2013

White pine torching with flame lengths reported to be 20–30 feet high. The Germann Road Fire consumed 7,499 acres and destroyed 104 structures (23 of them residences) in the Towns of Gordon and Highland in Douglas County and the Town of Barnes in Bayfield County. An estimated 350 structures were saved due to fire control efforts. The fire began around 2:45 p.m. on May 14, 2013, burning a swath nearly 10 miles long and a mile and a half wide before being declared 100 percent contained on May 15 at 9 p.m. The fire was started unintentionally from a logging crew harvesting timber on industrial timber lands. Learn more about the Germann Road Fire.

COTTONVILLE FIRE | 2005

This wildfire began on May 5 in northern Adams County. The fire rapidly spread through grass, needles and brush to the tops of the pine trees close by. Utilized resourced included 38 tractor plows, 25 forest rangers with Type-7 4x4s, three low ground units, six heavy dozers and almost 200 DNR personnel to control and eventually suppress the wildfire. Air resources cooled the flanks for ground crews and dropped water and fire retardant on structures. The fire was finally contained after 3,410 acres had burned. Nine year-round residences, 21 seasonal homes and at least 60 outbuildings were completely destroyed, but an estimated 300 buildings were saved.

CRYSTAL LAKE FIRE | 2003

On April 14, a wildfire began in northern Marquette County near the Lake of the Woods campground. Between 50 and 100 camper trailers in the campground and 24 homes and outbuildings in the area were directly threatened by the fire but ultimately saved with the help of 17 local fire department engines and tankers, DNR engines, bulldozers, aircraft and air tankers and private bulldozers. The fire eventually burned 572 acres and was determined to have been caused by debris burning.

WHITE RIVER MARSH FIRE | 1989

The White River Marsh wildlife area is a 12,000 acre property located in Green Lake and Marquette counties. A man hunting on the property filled a metal coffee can with charcoal to have in his tree stand to keep warm. On November 20 (the Monday of deer season), he wasn’t hunting and the winds were so strong it blew the tree over with the tree stand in it, which dumped the charcoal, resulting in a wildfire burning 4,261 acres.

EKDALL CHURCH FIRE | 1980

The Ekdall Church Fire began on April 21 and ran nine miles in less than eight hours. At its widest point, the fire front was 2.5 miles wide. Fifteen DNR tractor plow units, seven fire departments, 27 private, county and National Guard bulldozers as well as scores of volunteers and cooperators from other county, state and federal agencies were utilized in containment of the fire. While 73 homes, cabins and outbuildings were destroyed in the 4,654 acre blaze, another 65 buildings were saved as a result of firefighter actions. The cause of the Ekdall Church Fire was determined to be accidental in nature.

OAK LAKE FIRE | 1980

Over 2,000 firefighters worked the Oak Lake Fire, which began on April 22 and included 23 fire departments, 52 DNR fire trucks, 30 DNR tractor plow units and 52 federal, county and privately owned bulldozers. While 159 structures (homes, cabins and outbuildings) were lost in the fire, an estimated 254 were saved as a direct result of firefighter actions. While a cause was never proved for the Oak Lake Fire, it was thought to most likely be equipment related. Note that the Ekdall Church Fire and Oak Lake Fire burned over 16,000 acres in northwestern Wisconsin.

SARATOGA FIRE | 1977

Fifteen tractor plows, 18 bulldozers, 12 fire departments and about 100 men and women worked on the fire, which began on April 27 and burned a total 6,159 acres. Five homes, one house trailer, 10 barns and 84 out buildings were destroyed, but approximately 300 buildings were saved. Total damages were over a million dollars.

BROCKWAY FIRE | 1977

On the same day as the Saratoga Fire, a westbound Chicago and Northwestern train began setting fires three to four miles east of Black River Falls and continued igniting areas along the track almost all the way to the city before the train was finally stopped. Calls were immediately sent out to the adjacent areas for additional equipment, but because of the Saratoga Fire, these fires were short on tractor plows. The series of fires ultimately combined together to form one large fire, named Brockway. Later in the afternoon, an illegal cooking fire escaped and joined the railroad fires. The Brockway Fire was finally controlled after burning 17,590 acres with damages over $1,400,000, including the loss of 14 homes.

AIRPORT FIRE | 1977

The mop-up of the Saratoga and Brockway Fires was progressing rather well on the early afternoon of April 30 when two more fires broke out in the Black River Falls area. One fire started when a chain saw exploded in an area of heavy slash. Windy conditions drove this fire fast toward the Village of Brockway and Black River Falls, causing 1,500 people to evacuate. About 75 minutes later another fire, believed to have been intentionally set as a backfire on private property, started alongside the first fire. These fires ended up burning together, threatening to destroy dozens of homes in its path. With the assistance of 63 fire departments, no buildings were lost after the fire consumed 3,037 acres.

FIVE MILE TOWER FIRE | 1977

The Five Mile Tower fire burned in young pine. Around the same time the Airport Fire started, a family was camping just west of Minong in an area surrounded by jack pine when a spark blew out of their campfire. This fire would eventually burn 13,375 acres of pine forest and was about 15 miles long at its longest point. Embers were reported to have flown over a mile ahead of the fire, causing many additional “spot” fires. The fire was controlled after 83 buildings were destroyed, but over 300 buildings survived the fire.

WEST MARSHLAND FIRE | 1959

Fire conditions were extreme in Burnett County as the previous winter had practically no snow accumulation. On May 1, 1959, extra personnel were on standby at each station, as well as standby fire crews located at various points in the area. At 1:35 p.m., with 3 other fires burning at the time, the Grantsburg Ranger Station reported that they were heading to assist Grantsburg Fire Department on a structure fire. As units arrived, fire had spread away from the house and into a swamp. The fire was finally put under control at 9:30 p.m. on May 2 with the help of virtually every available fire fighter, fire department and heavy equipment in a four-county area, but not before burning 17,560 acres, and causing over $200,000 of forest and property damage.

PESHTIGO FIRE | 1871

On October 8, 1871, the deadliest wildfire in American history burned 1.2 million acres in Northeast Wisconsin. Burning through at least 17 towns on both sides of Green Bay, the Peshtigo Fire caused an estimated $169 million in damages. Twelve hundred lives were lost during the inferno, 800 of which perished in Peshtigo alone. It is said that the city of Peshtigo was lost in an hour. Survivors reported that the fire was caused by railroad workers clearing land for tracks, but we may never know if that is true or not. Because the Peshtigo Fire happened on the same night as the Great Chicago Fire, it is lesser known outside of the Great Lakes region.

Preparing your property for Wildfires

PREPARING YOUR PROPERTY

A unique wildfire danger is growing where homes and other buildings are built in areas of highly flammable vegetation, creating a condition called the wildland urban interface. Homes and cabins in the middle of forests, housing developments on the edge of pine plantations, lake communities surrounded by oak and pine forests or even homes next to grasslands all exemplify this condition. Buildings on sandy soils with an abundance of pine, oak and grass are especially concerning. Having undeveloped woodlands and fields in and around a neighborhood indicates that you, as the property owner, should prepare your home for wildfire [PDF].

AT-RISK HOMES

Think about your home or vacation property as you go through this checklist. The more items you check, the more likely you have a property at risk to wildfire and should take action to become “Firewise.”

I own a home in a rural area.

My home is in a wooded area.

Outside I see tall grass, oaks or pine trees.

Outside, I see more pine needles and leaves than lawn.

The soil around my property is sandy.

Burning takes place on my property or my neighbor’s property (campfires, leaf or brush burning, burn barrel use).

I, or my neighbor, dump wood ash outdoors.

I have heard about wildfires having occurred in the area.

There is a Smokey Bear fire danger sign in my community.

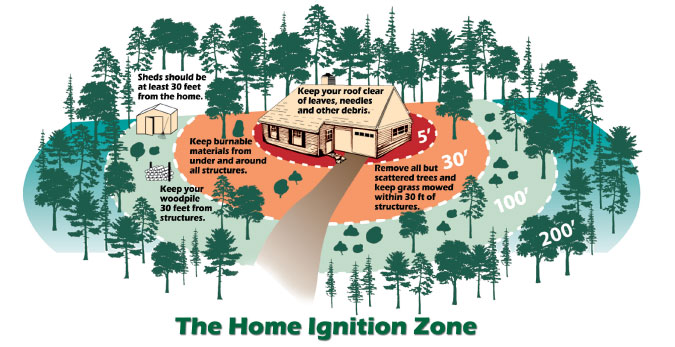

HOME IGNITION ZONE

The home ignition zone is your home and its surroundings out to 100–200 feet. Research has shown that the characteristics of buildings and their immediate surroundings determine the risk of ignition—that’s why preparing your home ignition zone is so important.

A graphic showing best practices for keeping homes safe from wildfire.

Since you, as the homeowner, are the only one who has authority to make changes around your home, you play a vital role in protecting it. The steps you take to reduce or change the fuels in your home ignition zone could determine whether or not your home survives a wildfire.

WATERFRONT PROPERTY

Many waterfront homes and cabins in Wisconsin are in areas prone to wildfires. Making your waterfront property Firewise does not mean having to sacrifice your shoreline stability, water quality or wildlife habitat. Oftentimes, the greatest wildfire protection you can offer your home is by removing “the little things” that can ignite, such as the leaves, pine needles and other debris that collects on your roof, in your rain gutters, next to your foundation or under your deck. The same places where this fallen debris gathers are the same places where flying embers will gather during a wildfire.

Remember that Firewise recommendations are just that—recommendations. They do not surpass covenants, ordinances, regulations or laws, including shoreland regulations. Wherever you own property, you should be aware of all applicable local, state and federal restrictions towards vegetation management.

DRIVEWAY ACCESS

If there’s a wildfire in the area, firefighters may need to reach your home. If firefighters cannot safely drive a fire truck to your house, they will have to come up with another plan. Perhaps they will park on the street and run hoselines down your driveway to your house or maybe they will send in a smaller truck to assess the situation. They will try to come up with a way to get to your home but it will likely take longer. As you can imagine, the faster a fire is extinguished the lower the risk of damage.

DOING YOUR PART

As the homeowner, you are the first line of defense when it comes to helping your home survive a wildfire. When you do your part to ensure adequate driveway access, it means that:

you have a safe route to leave your property when evacuation is necessary;

firefighters can locate your home and reach it quickly; and

firefighters have a safe place to work around your home.

Download our driveway access flyer [PDF] to get tips on how you can help firefighters protect your home during a wildfire.

View our driveway access video [VIDEO exit DNR] for additional tips and information.

BUILDING MATERIALS

When building a home or updating an existing one, simple adjustments to your design can greatly improve its ability to survive a wildfire. Check out our building materials brochure [PDF] to learn more about ignition-resistant building materials and construction techniques.

ROOF, SOFFITS AND EAVES

The roof can be a vulnerable part of your home because it provides a large horizontal surface where embers can land and ignite combustible materials. It is very important that roofing materials be fire-resistant and debris is removed from roof valleys, rain gutters and locations where the roof intersects a wall. Prune tree branches within 10 feet of your roof.

Eaves (the projecting roof edges), fascia, soffits and rain gutters are susceptible to flying embers and flame exposure. They should be constructed of non-combustible materials. Eaves should be boxed-in to prevent flying embers from entering.

EXTERIOR WALLS AND VENTS

Non-combustible siding materials such as brick, stucco and fiber-cement resist fire much better than wood. The exception is heavy timber or log wall construction as it takes a long time for large timbers to ignite and burn. Vinyl siding can melt, fall off and burn when exposed to flames and radiant heat, which can leave openings and make the home even more vulnerable to radiant heat, flames and flying embers.

Attic and under-eave vents that are unscreened can draw embers into the attic, igniting the structure from the inside. All vent openings should be covered with 1/4 inch corrosion-resistant wire mesh. Plastic and nylon mesh are not appropriate options as they can easily melt.

WINDOWS

Radiant heat from burning vegetation or a nearby structure can cause the glass in windows to break. This will allow embers to enter and start internal fires. Single-pane and large picture windows are particularly vulnerable to glass breakage. Install dual-pane windows with a minimum of one pane being tempered glass to reduce the chance of breakage during a fire.

GARAGE DOORS

Install weather stripping around and under the vehicle access door to reduce the intrusion of embers. If the garage is attached to the home, install a solid door with self-closing hinges between living areas and garage.

LESSON LEARNED

On May 14, 2013 a single spark from a logging operation in Douglas County ignited a wildfire that consumed 7,442 acres. Named the Germann Road Fire due to its location, the fire burned more than 100 buildings, including 23 homes and seasonal cabins. Another 350 buildings were in harm’s way, yet ultimately survived or were saved by fire suppression efforts. A research project conducted shortly after the fire provided us with an opportunity to share information with property owners on how to prepare their home and property for a wildfire.

HOW TO PREPARE FOR EMBERS

Defensible space is the area 30 feet around buildings that is maintained to limit the amount of flammable vegetation, debris and man-made objects that can become ‘fuel’ for a wildfire. You can prepare for embers with a few simple steps:

Rake leaves away from the side of your house and from under your deck.

Remove leaves and pine needles from your roof and gutters.

Remove flammable items (like wood mulch) from the five-foot zone nearest your home.

Move firewood at least 30 feet away from your home.